Japanese China from England (Part 1)

The world’s largest daikon ever harvested weighed exactly 69 pounds (31.3 kilograms)—more than three times the size of your average daikon.

I blinked at the rubber, life-size model of the record-breaking radish through the display case in the museum—it was the same size as one of those exercise balls for doing sit-ups. Given the chance to hug the vegetable, my arms would fail to reach around it fully.

Daikon are Japanese white radishes. That thinly-grated pile of nearly-tasteless white stuff garnishing your sashimi? (the stuff you touch with your chopsticks but really never eat)—that’s daikon. Planted at the base of a living, breathing volcano, where the deeply-soluble ash soil of Sakurajima lets rainwater dissipate quickly, daikon grows down—and out. Indeed, ash is the secret to growing oversize daikon, and the vegetables have become a symbol for the active volcano island of Sakurajima—even the streetlamps are made to look like daikons.

Businessmen have tried to market and sell jumbo daikon seeds from Sakurajima, but planted outside the dark snowfall of ash, the seeds grow into the same puny pumpkin size as every other typical, ungifted daikon. The Sakurajima daikon is special—it even has its own Facebook fan page–though it only has 4 fans (I became the 5thbecause honestly, I’m a fan).

Ash is in constant supply here. Almost daily, the Sakurajima volcano spews a remarkable stream of gray ash up into the atmosphere over Kagoshima, the southernmost prefecture of Kyushu, which is the southernmost island of “mainland” Japan. The brown-gray ash cloud erased half the sky in front of me and I wondered how people could cope with it falling day after day.

All morning, heavy ash had been falling on my head—like rain falls in England: a constant gray drizzle that seems little bother until after twenty minutes when you realize you’ve become totally soaked. In Kagoshima, I became gritty like a chimney sweep—I could feel the soot collecting on the back of my neck.

The active volcano is such a regular part of life in Kagoshima that special yellow bags are made available to the public for dumping their ashes, which they leave on the curb for pickup. A special ash truck carries out regular street cleaning, but even then, the ash builds up on rooftops, windshields, sidewalks and in my hair.

This year alone, Sakurajima has erupted 897 times. They count everything in Japan, for this is a land of numbers. The volcanic activity is measured and no matter how small, every explosive eruption is counted. The last major eruption took place in 1914 when the lava flow swept across the bay, fusing Sakurajima to the mainland. Although, the locals still see the volcano as an island, with ferry service to and from the city on a dressed-up Mississippi riverboat named Cherry Queen.

One of the last minor eruptions took place while I was gawking at the giant rubber daikon. I heard the excited schoolgirl chatter in the corner and rushed over to the seismometer just in time to watch the leaping yellow peaks of the digital needle on the screen. Thirty seconds later, an attendant took down the “7” on the wall and replaced it with an “8”: 898 eruptions this year.

In fact, during my stay in Kagoshima, I survived five measurable volcanic eruptions. (This after our little earthquake and hurricane back home and a wee typhoon in Hokkaido.) For the record, I learned that the creamy brown horse shampoo at the onsen works best for untangling those persnickety ash dreadlocks that form unwittingly in your hair.

But the ash is a gift to the region, really. It is Kagoshima’s falling ash that gave color to the region’s famous pottery.

Hold it—Stop there. Giant radishes—and now pottery? Just hand me an Ambien already.

Such were my disagreeable thoughts as my tour guide led me to another museum filled with gold-tinged Satsuma ware. I enjoy museums but try to live by the daily recommended allowance of two. This was number three and staring at glazed pottery with glazed eyes was not why I had crossed the ocean and come to Japan.

Luckily, I had a very good guide—an intelligent woman with a degree in linguistics from an American university and a masterful command of English. More importantly, she had haragei (literally “stomach art”)—the Japanese technique for non-verbal perception. Perhaps it is similar to gut instinct, except the Japanese actually teach and learn this stomach intuition as a skill. In this day of digital entertainment and social media, some Japanese parents are concerned that the youth have lost the ability to communicate—there is a push to re-introduce haragei as a subject in school, based on the education system of the samurai.

I suspect it was haragei that helped my guide realize that pottery was not my thing. And so, like any good guide does, she switched gears and told me a good, old-fashioned murder story:

Charles Lennox Richardson ran off to China when he was only 19 years old. Like so many young Englishman in Shanghai, he made his fortune as a merchant, trading things the Chinese wanted from England with things the English wanted from China. After five years of successful trade and now a rich man, he boarded a ship to return to England—only he stopped off briefly in Japan to sightsee with friends.

On September 14th, 1862 (149 years and one day ago), Charles and three friends were riding their horses down the Tokaido Road—the same imperial path that would later became the route of the bullet train. While they sauntered on their lazy Sunday afternoon ride in one direction, the entire traveling entourage (wife, concubines, porters, and samurai guards) of the Satsuma Lord Shimadzu Hisamitsu approached from the opposite direction. Despite a stern samurai warning to step aside (a show of respect), Charles must have been curious and ridden his horse a tad too close for comfort—something like a tourist crossing a police line to check which of the black cars in the presidential motorcade actually held the First Lady. As Charles approached one of the gilded palaquins, a samurai swung his sword and slashed the Englishman’s torso—he fell from his horse, severely wounded.

His friends were also wounded but fled with their lives, while Charles lay bleeding on the road. It was Hisamitsu himself who commanded the suffering Englishman be dealt the second fatal blow—a samurai himself, he saw it as the correct thing to do.

The British government referred to this unpleasant murder of one of their citizens as the Namamugi Incident and immediately asked for monetary reparations from the Satsuma lord in the neighborhood of 25,000 pounds sterling (more than three million dollars in today’s money). Satsuma refused, saying the Englishman had died for his disrespect—which was the law in Japan at the time.

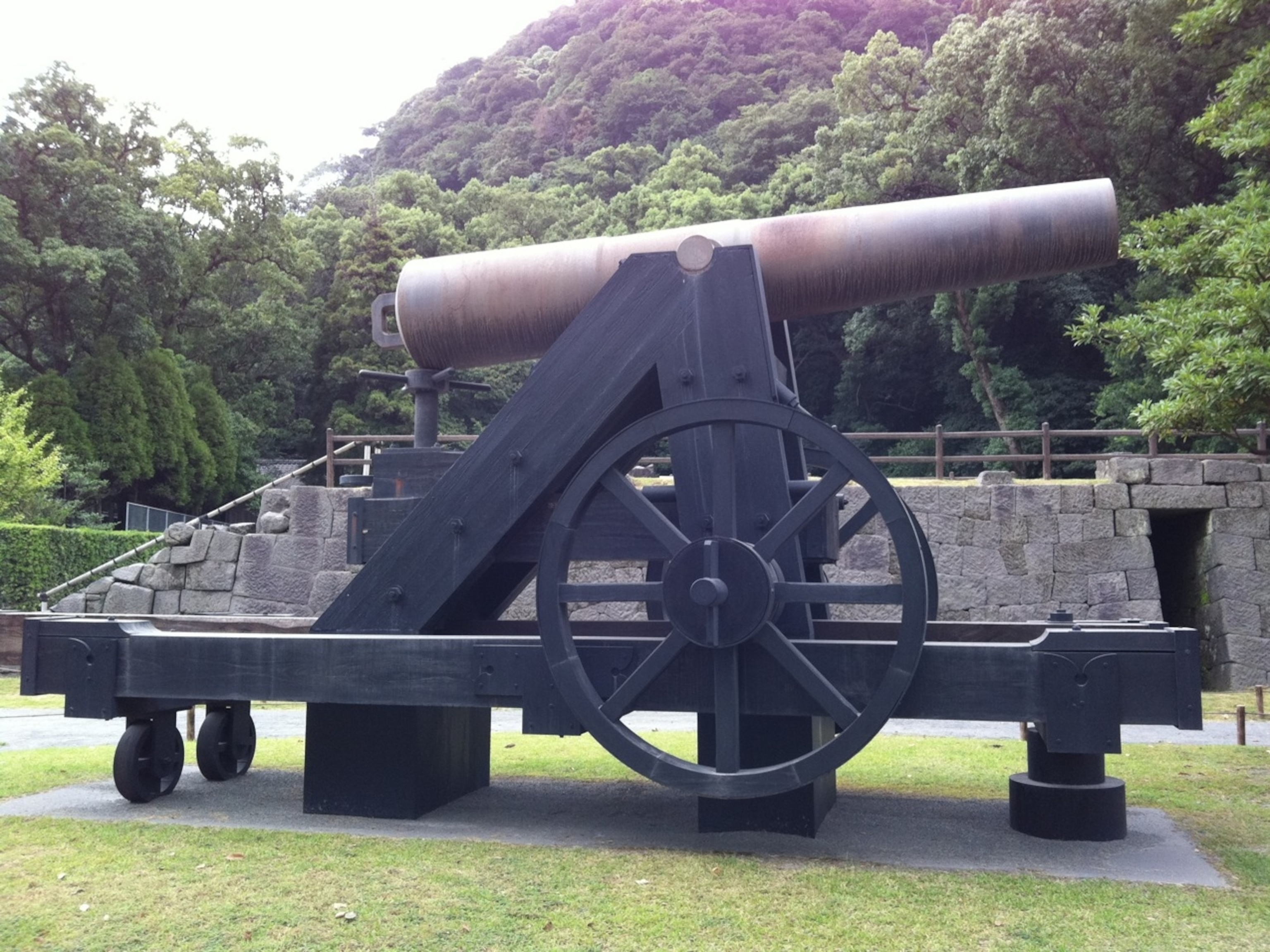

The British Navy responded by returning a year later and bombarding Satsuma’s capital city of Kagoshima–although like all war, the scuffle started small and escalated quickly. First the English seized three Satsuma merchant ships as “leverage” in negotiating the settlement for Charles, then Satsuma responded with a few first shots, after which the Brits burned much of Kagoshima to the ground.

Who actually won the two-day Anglo-Satsuma “war” is still uncertain. The Satsuma forces had far less ammunition than the British. The Japanese compensated for this lack of true force by shooting off a bunch of fireworks, a tactic that was successful in scaring the bejeezus out of the British navy. The Satsuma forces also had a few lucky shots that managed to kill both the British captain and his second-in-command. Over the next few days, the bloated, waterlogged bodies of British sailors washed ashore on the beaches of Ibusuki—the same hot black sand beaches where I had buried myself the day before.

A small local government had managed to beat the British navy, but at what cost? Kagoshima had been hit hard and the Brits would likely return with even more force. The Japanese who had fought in the battle knew that the British forces were stronger and better-equipped and that in the long run, a war would ruin them.

And so the government of Satsuma tried a different tactic—friendship. First they paid the money to the British government (which they borrowed from the Edo government and then never repaid, since the Shogun later fell from power)—and then began a long and concentrated effort of diplomacy.

Actually, it all began with a gift of oranges.

Four months after the battle, Lord Hisamitsu’s agents approached the British emissaries with the acknowledgment of the “irresistible superiority of [British] power” and the desire to “remain on friendly terms”. Along with these kind sentiments they gave a gift of fruit. A British officer described the exchange:

“They concluded their last interview with me by offering some trifling presents not the less significant of good will to the Admiral and myself among which I would especially remark some baskets of Satsuma orange which they desired might be presented to the Crew of the Flag ship.” (Letter of Sergeant John Neale to Lord Russell, December 30, 1863, Public Record Office, London)

Ah, but fruit is not a trifling present in Japan—I mentally corrected the British naval officer of long ago while reading his letter in my fourth museum of the day. The gift of fruit is serious business in this country—apples, plums, peaches, melons, grapes. I have seen how fruit is grown in this country, how it is treasured on the vine and how farmers aim to grow fruit with perfect shape, color, texture, ripeness and flavor. Fruit is a work of art in Japan and to present this kind of natural art to a friend is a sign of great respect and admiration.

I thought back to the years that I had lived in England—to the place where I first heard the word “Satsuma”. In England, Satsuma is not a place, but a tangerine—a very special tangerine where the peels slip off so easily and you can pop each sweet seedless slice into your mouth. They sell them in every market and grocery store and I love them.

It all went back to that gift of fruit on board an English ship in Kagoshima Bay. The tasty Satsuma tangerine was discovered by the British, seedlings were exported and grown into orchards around the world—and today there are four towns in America named Satsuma (Alabama, Texas, Florida, and Louisiana).

Satsuma, Japan is where satsuma come from. This is why I travel without a guidebook—because I like to happen upon these discoveries all by myself in situ. I had traveled to Kagoshima and by so doing, discovered the birthplace of the tangerines that kept me alive as a student in England.

Seeing baskets of satsuma for sale on the streets of Satsuma was purely Proustian for me—my body was in Japan but my mind traveled back to England and a time in my life when the whole world opened up.

Travel does that to people. The Satsuma government understood this, even back in the 1865, when, in spite of the central (Edo) government’s strict ban against travel outside Japan, Satsuma sent 19 young students to England for an education, in hopes that they would return and bring progress to Satsuma. This was no easy feat—ordinary citizens were not allowed to travel to foreign places due to strict policy of isolation. The 19 students were first smuggled to Okinawa and then China on a fishing boat, then made their way across to England via India and the rather new Suez Canal.

Japanese students in England was a big deal—like a moment of first contact between two very different cultures, followed by many more moments of mutual fascination. And while the Japanese government of Tokyo failed to be represented at the Paris Expo of 1867, the Satsuma government sent their delegation of 19 students, along with three geishas who, according to the Paris newspapers, were a complete hit.

Around the same time, Europe’s adoration of all things “oriental” leapt upwards, just like the little yellow seismometer on Sakurajima. Suddenly, they couldn’t get enough of Japan—and Satsuma was there to provide: tangerines, tea . . . and pottery.

******************************************

“French food is too salty for the Japanese,” he explained, shaking his head.

I was having lunch with Shimotakehara Tadataka, President and CEO of Hakusuikan, the hotel in which I was staying. (http://www.hakusuikan.co.jp)

Rather, I was having lunch in his Italian restaurant—Fenice—the one that Shimotakehara the CEO had designed and built himself.

“I have tasted many foods from many different parts of France,” he offered. “Their sauces are too salty for Japanese people,” he paused, “but Italian food is just the right amount of saltiness for us.”

Offering an Italian menu was good for business, which is almost entirely Japanese. We discussed food briefly, and then the businessman moved into the realm of social media, guessing at my interest.

“I have 4,000 Facebook friends,” he confessed, both proud and embarrassed. “What should I do once I reach 5,000?” he inquired aloud, clearly knowing the answer already.

“Start a fan page,” I answered, feeling like I was reading the line from a typed screenplay.

Shimotakehara-san was dressed in a suit, tie and designer shoes—playing the role of gracious host, feeding me a remarkable Italian lunch and spending his precious CEO time on me. In return, I was wearing shorts and a T-shirt, trying to contribute bits of wood to the barely-flickering fire of conversation.

Weather. I asked him about the weather in Kagoshima in winter. He replied like a businessman, “When the sun shines, we can play golf in short sleeves.”

And the Sendai earthquake last March? “What was it like here in Kagoshima?” I wondered, then wondered if it was too impolite to ask. I wonder that often here in Japan.

“I was in Tokyo that day, right in the middle of getting a shiatsu massage,” he laughed. “The masseuse ran out of the room but I wanted her to continue. I am quite used to earthquakes.”

“Here in Kagoshima we had a tsunami, but it was only five feet high—just a small one,” he held his hand to his chest—an acceptable tsunami height. Incidentally, he added, the real estate prices in Kyushu have jumped since March. When it comes to a place to live, Japanese people are choosing volcanoes over earthquakes and tsunami.

We talked about the volcano. There are 110 active volcanoes in Japan, eleven of them are here in Kagoshima. This is good. Volcanoes are the family business—Shimotakehara-san has bought up many of the hot springs in and around Ibusuki which he uses to feed the sand baths and his spa. The same spa that Boris Yeltsin visited ten years ago.

Yeltsin got us talking Russia and I discovered that for several years, Shimotakehara-san had served as head of the Mitsubishi chemical plant in Kazan. Finally, here was something that I could talk about.

“You speak Russian?” he quipped, in Russian.

“Da . . .” I answered and the conversation finally went airborne, albeit in Russian.

I learned many things about from Shimotakehara-san—how in Japan, the wedding traditions are more Christian, the funerals are all Buddhist, and New Year’s celebrations more Shinto. Also, that Japanese youth must be 18 to get a driver’s license, while the age of consent is only 13, and that one third of all the chicken served in Japanese KFC’s comes from Kagoshima.

Shimotakehara-san spoke fluent Russian and his English was perfect—the result of several years at Harvard, several more years in England and a long life living abroad as a Japanese businessman. He also speaks German.

He took command of the family company only two years ago, but already has made many significant changes. This has caused some tensions, especially with his older brother. “My brother loves all things Chinese,” he said, “But I had to fire all the Chinese musicians—too much money.”

He had mentioned this older brother already before lunch when he had taken me upstairs to see their private museum.

“My brother also has a passion for Chinese ceramics,” he explained. With one hand he held his concentrated forehead—as if nursing a headache. He swept his other hand swept across the room, opening my eyes to display case after display case of ceramics: vases, urns, porcelain camels, elephants, teacups, figurines.

I have been to the Louvre and other museums filled with ceramics and objets d’art. I have seen precious things—I have also been to garage sales and seen tables of junk. When it comes to porcelain cats and cupids made of clay I am a total ignoramus—honestly, it all looks like Home Shopping Club to me.

It was the day after my four-museums-in-one-day marathon back in Kagoshima, and already I found myself in another museum filled with the exact same kind of pottery—Satsuma ware.

Satsuma pottery used to be a booming business. 19th century Europeans wanted it badly and Satsuma responded on a huge scale. The fragile porcelain has a golden hue to it and was decorated with Japanese figures and landscapes, trees and dragons. This specific ceramic artwork became the must-have decoration in the distinguished Englishperson’s home and it made Satsuma rich.

But Satsuma ware did not originate in Satsuma—like all china, it comes from China. I listened carefully as Shimotakehara-san explained how Korean and Chinese craftsmen carried the knowledge of pottery to Satsuma and how it developed from there. He walked me from one piece of pottery to the next, explaining the intricate history behind each of these dishes. I peered down at the tiny labels standing in front of each dainty pot, announcing each item’s age in centuries and dynasties. These ceramics were not mere antiques—these were true antiquities.

I know nothing about Ming vases but after several hours spent looking at them up close, I do think I prefer the Qing dynasty. It was a Qing dynasty bowl that made me stop and stare—an 18th century piece glazed a very gentle lavender color. Suddenly, I wanted to reach through the glass and touch it. That bowl was so beautiful.

But there was thick glass all around and the blinking red lights of an alarm system. Even tiny pots are worth a huge fortune.

“See that one there,” my host pointed. I looked at a Ming vase—a real life, honest-to-goodness, cliché-free, 15th century Ming vase, blue and white, with its liquid-like rim floating at the top of its perfect round form.

“A similar one just sold at Sotheby’s for $2.45 million,” Shimotakehara-san hushed the words.

Then he pointed to a teacup, so tiny and fragile and white, I thought I would break it simply by staring at it through the glass—but my host tapped the glass as he pointed to it, smiling.

“This one! Ah, this was one I showed to the man from Sotheby’s,” he laughed, “and that man said only one word to me: ‘Problem’”.

The dealer had sold the exact same cup to the British Museum for well over a million dollars, telling them that this was the only one like it in the world. And the brother of Shimotakehara-san had that same teacup in his priceless collection.

Yes, the world of antiques is filled with fakes. For the last thousand years, imitations have been made to protect the real treasures. In Japan, ceramics were given as gifts of gratitude—if and when you received such a gift, the first thing you did was to make a copy. You displayed the copy and hid the real dish—not to prevent theft by burglars, but from your overlord. If your master entered your home and spotted your treasured vase or bowl, he had the right to take it from you. Hence, the market is now flooded with imitations, but even these copies are precious, explained my host—some of them more than 500 years old.

The dishes do seemed to have held up remarkably well. I wondered what would happen if you stuck one of them in the dishwasher, but I did not ask him this. By now, I had become legitimately intrigued by this strange world of Chinese ceramics in Japan and the delicate art of dishes.

I gazed at another small bowl—pale blue, but not just blue: the color was both soft and complex, mesmerizing.

Sometime in the 10th century, Emperor Chai Shizong of the Zhou Dynasty gathered his artisans and ordered them to create a ceramic glaze that was the same color as the sky just after rain fall. After many attempts, they succeeded. This bowl, made in the 12th century (Song Dynasty) was coated in this same glaze, known as Ru Guan. Only thirty-four known pieces glazed in this color remain in the world, five of them are in Japan. My mind wanders to my very worst skill—math—and I began to multiply the millions of dollars of ceramics held in these rooms. Then erasing the figure entirely—these were priceless. That was the point of collecting them.

Amid all the pottery was something else—a single paper wall-hanging scribbled with black paint calligraphy, displayed under the dimmest light and behind glass.

“What does it say?” I asked. After two weeks in Japan, I am still functionally illiterate. Like an eager child though, I want to know what all those painted scribbles mean.

“It is a poem. A Chinese poem,” Shimotakehara-san told me. Written by Saigo Takamori himself—Japan’s Last Samurai. Saigo Takamori came from Satsuma and led the samurai rebellion against the Emperor in 1877. He failed and disappeared in the final battle—there are too many rumors about his death to know what actually happened. After two days in Kagoshima, I felt like the open-ended life of Japan’s last samurai left an intangible thread tied to Satsuma’s noble history—that even in 2011 there was this sense of difference in Kagoshima—political, cultural, even linguistic.

I am told that Kagoshima dialect is filled with old-time sayings, some of which have survived for centuries. The quaint expression “Ryuku seems far away,” means that one’s tea is not sweet enough. Satsuma conquered Ryuku (Okinawa) in 1609, after which the island paid its tribute in shipments of sugarcane. Other trade followed, including pottery and tea. Indeed, Okinawa has been Satsuma’s back door into China and vice versa beyond into Japan. For example, the purple sweet potato sold all over Kagoshima (even as soft-serve ice cream) is called karaimo, meaning “China potato” while throughout the rest of Japan it’s called Satsuma imo or “Satsuma potato”.

To this day, Okinawa is still administered from Kagoshima. In the later afternoon at Shimotakehara-san’s hotel, I looked out across Kagoshima Bay, my head filled with the dizzying history of this one little place. To the north sat Sakurajima, the impending and constant volcano, with its brown-gray ash cloud billowing upwards. To the south, large ships glided across the sea, carrying cars and passengers to Japan’s southernmost outpost, Okinawa. The sky was clear and the water on the horizon shone slightly turquoise, hinting at the tropics just beyond.

Go Further

Animals

- How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Environment

- Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?

- The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

History & Culture

- Meet the original members of the tortured poets departmentMeet the original members of the tortured poets department

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Travel

- This tomb diver was among the first to swim beneath a pyraamidThis tomb diver was among the first to swim beneath a pyraamid

- Dina Macki on Omani cuisine and Zanzibari flavoursDina Macki on Omani cuisine and Zanzibari flavours

- How to see Mexico's Baja California beyond the beachesHow to see Mexico's Baja California beyond the beaches

- Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?