The Farm

After three weeks of traveling in this province, I feel safe reporting that Ontario is a big city, an endless wilderness, and everything in-between—a latticework of lakes, forests and fields, small towns, and tundra, too.

Ontario is also lots and lots of farms. Driving the highways of southern Ontario is an exercise in passing by farms, one right after the other. In certain areas, you can measure distances by counting the silos. Sometimes, white lettering spells out the farm family’s name on the front of the barns. I’ve often noticed old-fashioned, split-rail fences that parcel out squares of land, separating the shorter grass from longer grass, the sheep from the cows, one man’s cows from another’s.

Hours of farm country might dull some drivers into a zone of boredom, but I find it all very picturesque. In summer, Ontario’s pastoral landscapes are bright with life, both plant and animal. What’s more, farms are so numerous and make up such an overwhelming majority of the scenery that, as a traveler, you really can’t overlook them.

In some ways, each farm is the same—there is always a house, a dog, and a barn—and in other ways, they are different: some grow corn, others wheat or soybeans, some have Jersey cattle, some have big grain elevators and heavy machinery, some look clean and new, some look tumbledown and in need of a good shovel or a can of paint.

Traveling in Ontario, I wanted to visit a farm—I was eager to explore this single unit of land from which so much of this province is built. Normally, I would just show up and start shaking hands with the farmer, but because this is Canada and Canadians are so gosh-darned polite, I decided I would try and be polite and call ahead.

The man I called (or rather, wrote to) was Iain Reid, a young Ontarian who grew up on a farm near Ottawa. Like so many kids from farms, he went away to school and then moved to the big city. After years of urban life in Toronto, Iain Reid was offered a temporary job in the capital. Instead of finding a small apartment in the city, he moved back to his parents’ farm for the summer. Summer melted into fall, and then it was winter—in the end, Iain stayed and helped out on his parent’s farm for a full year.

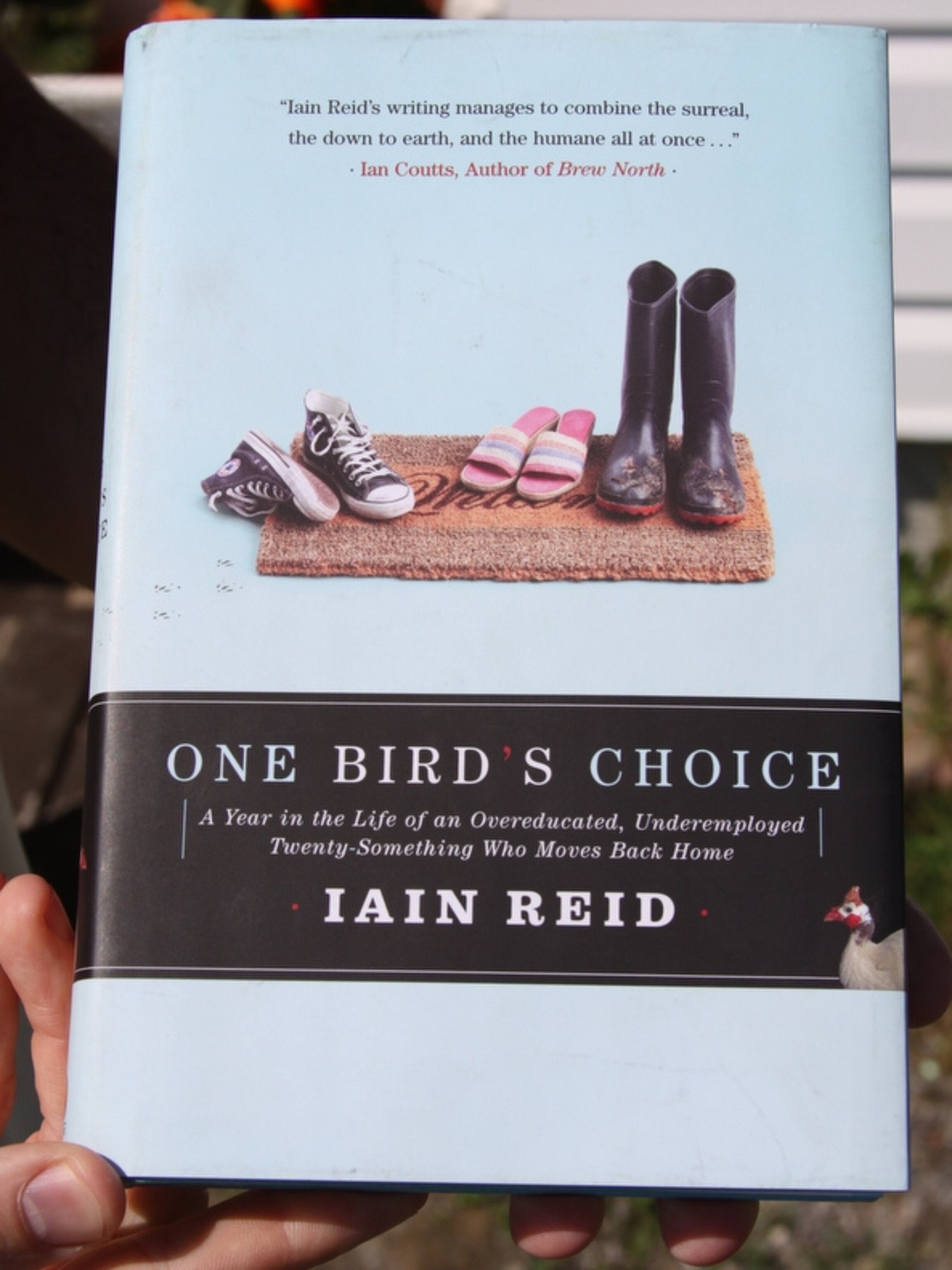

In the end, he also published a book about that year in his life, entitled, “One Bird’s Choice”. The book is about many different things, really—life after college, the quarter-life crisis that so many young people face, and life at home as an adult—but it’s also a memoir of a year on a farm in Ontario. I read Iain’s book long before I ever planned on coming to Ontario and enjoyed its rich simplicity and his descriptions of day-to-day life on a farm. When I realized I’d be going to Ottawa, I wrote Iain by email and meekly asked, might I come see his parents’ farm?

Iain and his parents kindly agreed, and being the hospitable Canadians they are, his mother and father invited me for dinner—and then to stay the night and then to stay for breakfast, too.

Lilac Hill is not a dressed-up tourist farm with arrow signs that point the way. It is still very much a hidden private place and Iain wants to keep it as such, but I can tell you that it only took me 40 minutes to drive there from downtown Ottawa. The Ottawa Valley is a beautiful region, dotted with historic farms that are connected by tree-lined lanes. Aptly named, a wall of ten-foot-high lilac bushes borders Lilac Hill. The house and barn are situated on a kind of hill, surrounded by sweeping fields in every direction and the breeze blows with a sweet scent of hay and flowers.

Upon arrival at Lilac Hill, I was greeted by Nana, a polar bear of a dog who still thinks she’s a puppy. The 5-month-old Great Pyrenees jumped right up on me, tackled me to the ground and then splashed her tongue down my cheek and neck (Welcome to the farm!)

Iain saved me from so much puppy love and introduced me to his mother and father. I have to say, it is pleasantly strange to meet the characters from a book in real life—a rare privilege. In fact, arriving at the farm felt a lot like I was stepping right into Iain’s book.

The farmhouse on Lilac Hill was built in 1834, a solid log home hewed from the Canadian woods, with walls stuffed with moss for insulation against cold Ottawa winters. Time and technology have added layers to the house, as well as several new additions, and today Lilac Hill is a rambling home that is both cozy and expansive. Every doorway leads to another room with an inviting corner armchair and shelves of books. It is the country home of an English professor and the home of his wife who once ran a catering business out of her farmhouse kitchen. Instantly, I could feel that this was a house meant for enjoying family, good books and good food.

The Reid family moved to Lilac Hill in 1984 when Iain was just five years old. The farm represents his formative years, and as his book details, a year of his young adult life. Neither of his parents were full-fledged farmers. In Canada, these small holdings are called hobby farms—though caring for ten sheep, a flock of ducks, a coop of chickens, guinea hens, and a dog and two cats seems far more intensive than building model airplanes or crocheting.

A log-beam barn sits in the back of one field, like a life-size Lincoln-Log house. A century of Ontario weather has opened a few of its seams and added a touch of arthritis to the walls, but it’s a solid structure that was built to last. Inside, the air was dark and musty, with a few cracks of light pouring in from the open gaps between logs. There was history in this barn—over a hundred years of history, happening one season at a time: planting, growing, harvesting, storing. I thought, “You haven’t been to Ontario until you’ve stood inside an old barn.”

The silence of the barn is the silence of the country and that peaceful quiet crescendoed long into the night. Once the animals went to sleep, there were no sounds left to be heard. I followed the animals’ example and went upstairs, laid my head down on my pillow and waited, listening in the dark. There were no sirens, no whoosh of traffic, no ticking or tocking of clocks or watches, no shrieks from any neighbors’ late-night revelry. There was no creaking, either—the house at Lilac Hill was built right on bedrock and has settled long, long ago.

I listened to the farm’s black silence for a full minute before turning comatose. I only blinked at the pink light of dawn and double-checked my phone, only to confirm that I had in fact slept for eight straight undisturbed hours.

My Ontario farm breakfast began with brown eggs gathered with a straw basket from the chickens in the yard. The bacon was from the farm down the road, the creamy honey on my toast was from the “next-door” neighbors, whose house I still couldn’t see despite searching the green horizon with a hand over my eyes.

Iain’s mother and father were gracious hosts with a golden supply of farm stories to share. In all my travels, a breakfast table on a family farm is about as warm and friendly a place as you can find. And then, as if on cue, the local sheep shearer arrived wearing high rubber boots, white T-shirt and blue cap. It just so happened that this was the day when all the sheep got their haircut for the summer and luckily, I got to watch it all.

Again, I felt like I was living a day in the life of Iain’s book, which is a magical feeling to have. I blame books for so many of my travel dreams—If I’ve read some story that happened somewhere else, I always end up longing to travel there—to experience all the same things described in someone else’s story.

A true sense of place is the greatest gift an author can give us as travelers. We talk of Hemingway’s Spain or Austen’s England as if they are a standard of authenticity, even though both writers are long dead and the worlds they painted with words have become nostalgia and fantasy rather than an actual destination.

Reid’s Ontario is still real, given that his book is still warm from the printer. And yet, one day, this world of Ontario farms may follow suit and disappear into mere memory and dreaming. Already, the Ottawa suburbs are pushing in around Lilac Hill—land has been parceled out for subdivisions and fewer farms are able to stay up and running as working farms.

It is easy to romanticize farm life as picturesque and charming when real farm life is often blood-stained, stressful and piled high with manure. Even so, “One Bird’s Choice” brought the farmland of Ontario’s Ottawa Valley to my attention—as an outsider, I’m not sure the narrator realizes all that he has captured in his pages. Besides his own life, he’s captured a time and place that defines a giant piece of this province, its traditions and its history of homesteading.

I ask Iain about this—what about the sense of place in his book? How does he feel about all of it now—the farm, the region, and his province as a whole?

He answers in three words, “Ontario is home.”

Go Further

Animals

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them? - This biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the AndesThis biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the Andes

- An octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret worldAn octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret world

- Peace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thoughtPeace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thought

- Why are these emperor penguin chicks jumping from a 50-foot cliff?Why are these emperor penguin chicks jumping from a 50-foot cliff?

Environment

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

- Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security, Video Story

- Paid Content

Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security - Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?

- Are synthetic diamonds really better for the planet?Are synthetic diamonds really better for the planet?

- This year's cherry blossom peak bloom was a warning signThis year's cherry blossom peak bloom was a warning sign

- The U.S. just announced an asbestos ban. What took so long?The U.S. just announced an asbestos ban. What took so long?

History & Culture

- This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?

- See how ancient Indigenous artists left their markSee how ancient Indigenous artists left their mark

- Why Passover is one of Judaism’s most important holidaysWhy Passover is one of Judaism’s most important holidays

- Is this mass grave a result of contagion—or cannibalism?Is this mass grave a result of contagion—or cannibalism?

- The surprising story of how chili crisp took over the worldThe surprising story of how chili crisp took over the world

- We swapped baths for showers—but which one is better for you?We swapped baths for showers—but which one is better for you?

Science

- Why outdoor adventure is important for women as they ageWhy outdoor adventure is important for women as they age

- 4 herbal traditions used every day, all over the world4 herbal traditions used every day, all over the world

- Ground-level ozone is getting worse - here's what that meansGround-level ozone is getting worse - here's what that means

- Would your dog eat you if you died? Get the facts.

- Science

- Gory Details

Would your dog eat you if you died? Get the facts. - In a first, microplastic particles have been linked to heart diseaseIn a first, microplastic particles have been linked to heart disease

Travel

- Why it's high time for slow travel in Gstaad

- Paid Content

Why it's high time for slow travel in Gstaad - How citizen science projects are safeguarding Costa Rican pumasHow citizen science projects are safeguarding Costa Rican pumas